-Northside Drive to the west (formerly Davis Street);

-Mitchell Street/Martin Luther King Jr. Drive to the south;

-The Georgia World Congress Center to the north (where a portion of Foundry Street used to be);

-Elliott Street to the east, but it's complicated...

Streets that used to run through the block include Mangum Street (still kinda does), Haynes Street, West Hunter Street (now Martin Luther King Jr. Drive, a portion of which remains on our block), Rhodes Street, and Magnolia Street. Plus a handful of alleyways.

In the image below, both Mangum and Elliott Streets run beneath the bigger elevated streets and into underground parking decks.

|

| #SecretButtholes |

Clear enough? Please stop crying…

On our trusty old 1871 bird’s eye view of Atlanta, we see a grid of sparsely populated blocks with some dwellings, possibly some stores, trees, and lovely rolling hills.

|

| 1871 |

The 1878 atlas paints a similar--albeit less aesthetic--picture of the area.

[Note: The following image and many others like it are composites I created in order to get all the blocks together in one image. Some things might not line up perfectly.]

|

| 1878 atlas (composite) |

Sixth Baptist started in a small wood building here in 1874. We will cover this church in more detail later.

Right now, let's turn our attention to Friendship Baptist...

The church grew out of a congregation of enslaved people at Atlanta’s First Baptist Church on the corner of Forsyth and Walton Streets in the Fairlie-Poplar District. In 1848, the congregation was granted dismission to worship separately from the white parishioners and form their own congregation called African Baptist Church (though the congregation would continue to worship at First Baptist and under white clergy and parishioners’ supervision). In 1862, Frank Quarles was formally ordained as the church’s first Black minister, and that year is officially cited as its foundation.

After the Civil War and Emancipation, First Baptist became a less welcoming location for African Baptist Church, in part because the building itself was damaged during the war, but also because the white congregation was increasingly hostile. African Baptist formally left First Baptist in 1866 and changed its name to Friendship Baptist Church. Since property was scarce after the war, the church was initially housed in a boxcar on First Baptist’s property, but later that year Reverend Quarles had a church built on Haynes and Markham (just south of our area). Quarles then set out to have a new permanent church constructed here at Mitchell and Haynes in 1871.

|

| Friendship Baptist Church, undated Atlanta History Center | Kenan Research Center |

|

| Spelman College Archives |

The Atlanta Baptist Seminary didn’t stay in Friendship Baptist’s basement for long. By December 1879, a two-story brick building with a bell tower was built for the school a couple blocks east on the corner of Elliott and Hunter. The school didn’t stay in that building terribly long either, moving to its present location in 1885. The Female Seminary moved out in 1883. Both schools adopted their better-known names after settling outside this block.

|

| 1881 City Directory |

Reverend Quarles’ efforts to acquire property and construct a new church for Friendship Baptist proved effective but costly. When E. R. Carter became the second pastor in 1881, the church was $3,000 in debt. But the congregation had grown from under 30 members before the Civil War to over 1,500. Carter worked hard to relieve the church of its debt, and Friendship Baptist was eventually able to sponsor a variety of important social services and fund The Carter Home for the Aged.

Georgia Tech's Building Memories series has a nice overview of Friendship Baptist if you'd like to learn a bit more.

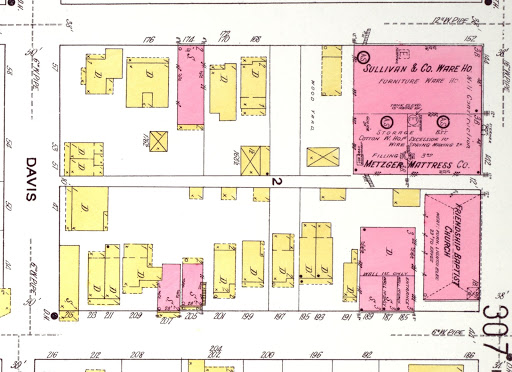

Moving on to the 1892 bird’s eye view and Sanborn map (of which we only have the southeast corner), we see the area is a bit more densely populated with some larger commercial structures cropping up.

|

| 1892 birds eye view |

|

| 1892 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map (composite) |

On the eastern side of the block, we see the Willingham & Company Sash, Door, and Blind Factory (aka Willingham Lumber Company, aka E. G. Willingham & Sons). It's #57 in the birds-eye view.

|

| The Atlanta Constitution | April 6, 1890 |

|

| E. G. Willingham The Atlanta Constitution | Sept. 7, 1910 |

Back to the 1892 maps, we have The May Mantel Company (sometimes spelled Mantle) just south of Willingham & Co (it's #35 in the birds-eye closeup above).

The main building was built in August of 1890 and was apparently quite lovely. It was constructed using only local materials: bricks from the Chattahoochee Brick Company and wood sourced entirely from Georgia. It was three stories: the first floor was the store, the second floor was offices, and the third floor was storage. Property and construction all together cost about $12,000.

May Mantel Company’s president, George S. May, was born in Ohio in 1852 and studied for a time in Germany. He visited Atlanta in 1881 and saw enough opportunity for business that he decided to move here. He invested in a lot of real estate and founded the May Mantel Company around 1890. May lived on Ponce de Leon Ave and had a summer house in Kirkwood called Villa Maia. He died in New York in 1914.

The following ad from The Atlanta Constitution is amusing to me for its reassuring “Everything will be all O.K.”

By 1895, though, everything was not all O.K., as the company was behind on rent and couldn’t pay its employees. It was bought out by J. Cundell later that year to be renovated and reopened, but I found no mention of it after that.

After he retired (failed at business?), May served on the sanitation committee for the Chamber of Commerce. An article in the March 17, 1912 Atlanta Constitution details one of his recent trips back to Berlin, where he marveled at the cleanliness of European streets compared to Atlanta’s:

“Civic cleanliness is a kind of insurance against plague and pestilence, and the dire consequences thereof, in the same way that filth and insanitation are an invitation for them to come and abide with us… Hercules cleaned the Augean stables by turning the Tiber through them. Our [sanitation] chief would no doubt accomplish the same trick with the Chattahoochee if he could make it flow up hill ‘and faith we shall need it’ if the Constitution’s efforts to educate cleanliness into the public are a failure.”

Moving onto the 1899 Sanborn map, we see all the dwellings lining the streets, plus some more noteworthy structures.

|

| 1899 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map (composite) |

First, we see that the Willingham Company is gone, as the big vacant area on the east side (with the compass rose) was once theirs. Second, the May Mantel Company has been replaced by the S. M. Truitt & Son Coal and Wood Yard. No idea what happened to J. Cundell.

Let’s move on to Sixth Baptist, which I briefly mentioned earlier.

|

| Temple Baptist Church with pastor Rev. A. C. Ward, undated Atlanta History Center | Kenan Research Center |

In November 1906, Ward’s neighbor at 120 Mangum, W. E. Wimpy, rented his property to a Black woman named Cassie Stephens. This angered some of the white neighbors, and with help from Atlanta Mayor James G. Woodard, Ward and his church succeeded in having Mr. Wimpy censured and Ms. Stephens evicted from the property. Temple Baptist passed a resolution (printed in The Atlanta Constitution on November 30) condemning Wimpy’s actions as “improper, unnecessary, exceedingly dangerous, jeopardizing to the peace of this community, and a flagrant insult to its white people.” This would have been just two months after the Atlanta Race Riot, during which at least 25 African Americans (likely more) were murdered at the hands of white mobs.

The following year, Temple Baptist parishioners were again opposed to new neighbors when the Gate City Terminal Company was planning freight terminals for the Atlanta, Birmingham & Atlantic Railroad to the block(s) just north. An estimated 1,500 homes total were to be destroyed to make way for the tracks and terminal. The church argued that the noise and soot from the railroad, road closures due to construction, and loss of residents would all interfere with their services. The case went to the state supreme court with Gate City ultimately winning in 1908. Reverend Ward resigned as pastor later that year.

With the opposition squashed, the Atlanta, Birmingham & Atlantic (AB&A) Railroad became the newest railway in town. Founded by Henry M. Atkinson, co-founder of what would become the Georgia Power Company, the railroad was to run from Birmingham to Brunswick, where steamships operated by the company would then ferry passengers and goods to further destinations along the coast.

|

| The Atlanta Constitution | June 14, 1908 |

The first passenger train chugged to Atlanta in June of 1908, stopping at Union Station. The terminal on our block was used for freight trains, and the company's main headquarters was located at the corner of Fairlie and Walton Streets (not here). At some point the railroad’s name changed to Atlanta, Birmingham & Coast (AB&C).

|

| AB&A Passenger Train at Atlanta's Union Station | June 19, 1908 Atlanta History Center | Kenan Research Center |

This brings us to the 1911 Sanborn map and the 1919 bird’s eye view, where we can see the central blocks have been significantly altered by the AB&A railroad, and Mangum Street north of Hunter Street has shifted to the east. The new train tracks coming in from the north were elevated on an embankment, which meant Foundry and Magnolia now had tunnels passing underneath.

|

| 1919 Birds-Eye View |

As we can see in both maps, the railroad brought a lot more commercial properties to the area. We’ll just take them one at a time starting with Frank G. Lake and his lumber company.

|

| 1911 |

Lake’s lumber company starts off on the east side of Mangum in the 1911 Sanborn map, but moves to a larger operation on the west side of Mangum near the train tracks by 1919's birds-eye view.

|

| 1919 |

|

| 1919 City Directory |

Mr. Lake was born in Macon in 1871 and moved to Atlanta in 1880. He founded his lumber company in 1898 and was active in various organizations and civic duties. He was a Mason, a Shriner, and yes, a member of the Concatenated Order of Hoo-Hoo, a forestry/lumber industry fraternity.

|

| Frank G. Lake, ca. 1957 Old Man Hoo-Hoo |

Mr. Lake was also a member of the Atlanta Historical Society and served on the Atlanta Board of Water Commissioners for the (now Old) Fourth Ward. He retired in 1945 and died in 1957.

Next up let’s talk about another Frank on the block: Frank E. Block.

|

| From The City Builder | July 5, 1923 Atlanta History Center | Kenan Research Center |

Block was a candy and cracker manufacturer (”The Cracker King,” and no I did not make that up) born in St. Louis in 1844. He came to Atlanta in 1870 and started his candy and cracker manufacturing business in 1873, which soon became the largest in the South. He was also an officer of Atlanta National Bank and at one point was president of the Georgia Railway and Electric Company (the future Georgia Power Company). He died of pneumonia in 1920.

|

| The Atlanta Constitution | Dec. 20, 1908 |

His house was on Peachtree Street one block south of where the Fox Theater stands today. Maybe one day I'll do a Block Party about the block with the Block House.

|

| Frank E. Block house, undated Atlanta History Center | Kenan Research Center Not on this block...forget you ever saw it. |

In the 1911 Sanborn map there’s a small building on the corner of Hunter and Mangum labeled “Structural Iron Works.” This was the Atlanta Structural Steel Company, which appears to have been here from around 1909 to 1914. It looks like the Frank G. Lake Lumber Company replaced it in the 1919 birds-eye view.

|

| The Atlanta Constitution | Nov. 12, 1909 |

Moving on to McCord-Stewart and H. L. Singer on the 1919 birds-eye, this building was a row of warehouses that popped up sometime after 1911 (they don’t appear on that year’s Sanborn map) along the railroad.

|

| The Atlanta Constitution | Feb. 12, 1905 |

|

| The Atlanta Constitution | Dec. 2, 1924 |

McCord was born in 1854 in Jackson, GA, where as a boy he watched while General Sherman’s troops searched his home and burned the town during the Civil War. He moved to Atlanta in 1885, starting his own company the following year with three traveling salesmen and three office clerks (maybe one of them was Stewart?). By 1916, the company employed about 100 people. McCord, whose nickname later in life was “Uncle Henry,” died at his home on Ponce de Leon Avenue in 1943 (maybe Stewart never existed?).

|

| Henry Y. McCord The Atlanta Constitution | Nov. 8, 1942 Photo by H. J. Slayton |

Next door was another wholesale grocer, H. L. Singer & Co., founded by Henry Leon Singer. During Georgia’s prohibition era, Singer marketed a non-alcoholic beer called ‘Pablo’ that according to the April 8, 1917 issue of The Atlanta Constitution “contains all the healthful and tonic properties of hops with none of the harmful alcohol contained in beer.”

|

| The Atlanta Constitution | Nov. 1, 1914 |

|

| Note Friendship Baptist Church directly in front of the building |

Wiley Candy Company was founded by Robert M. Wiley, who was born around 1866. Formerly an employee of the Nunnally Candy Company, Wiley opened his own factory on Marietta Street in 1897, moving to his new factory and headquarters here on Hunter and Haynes in 1917. Five years later the building caught fire and was considered a total loss, with $60,000 in equipment reported destroyed (adjusting for inflation, that’s like a hundred billion dollars or something). I couldn’t find any specific mention of the candy company after this, so the fire might have been the end of it. Wiley died in 1941.

Another fire broke out May 20, 1932, probably starting in a vacant house on Haynes. This time it was the building’s sprinkler system that saved Metzger from going up in flames. Eventually, though, the company’s assets were sold in 1940 after Metzger died.

Back on the east side of the area we have the Morrow Transfer Company.

Morrow Transfer was a hauling, excavating, moving, and storage company. Their main office was on Alabama Street, and their location here was their garage and stables (they used trucks and mules for hauling). The company was founded by James W. Morrow, a Monroe native and Confederate captain who served as Fulton County Sheriff in the 1890s.

|

| The Atlanta Constitution | June 9, 1913 |

At Magnolia and Haynes, A. A. Wood & Sons was a machine shop and patent office founded by Albert A. Wood and his sons Albert P. and Edward. The Wood family came to Atlanta from New York in 1876. Albert A. died in 1915, and Albert P. took over as president of the business until he died in 1938. Edward died in 1922.

In 1918, Mount Vernon Baptist, an African American congregation, purchased the Temple Baptist property. They initially formed in 1915 when three men approached Rev. E. D. Florence about opening a church in a storefront on Markham Street, just south of where we are. Florence had previously been holding church services in a tent on his property. Mount Vernon Baptist would be an important institution in the neighborhood for many years to come. Moving forward, African Americans would make up an increasing majority of the area's residential population.

They planned a $2 million renovation and expansion, which would have included buying adjacent land and duplicating one wing of their massive New York factory. That didn't end up happening, which we will get to later.

The next two maps show the area in 1928 and 1931.

Continuing our tour of the area’s businesses, we see that Frank Lake’s lumber company has moved again to the western portion of the block near where A. A. Wood & Sons used to be.

We also have some new tenants in the commercial warehouses on Haynes Street (where McCord-Stewart and H. L. Singer were). They aren't listed on the maps, but the addresses help us figure out what was there.

First, at 31 Haynes was the Florence Stove Company. Based out of Massachusetts, the company opened a branch in Atlanta in 1922 on Alabama Street. This location here looks like it was a warehouse and showroom for their oil ranges in operation around 1935.

|

| The Atlanta Constitution | May 12, 1935 |

|

| The Atlanta Constitution | May 26, 1935 |

Next up, the M. & M. Warehouse Company was located at 29 Haynes. Founded by Henry W. Gullatt, the company was initially a commercial storage facility where businesses could store surplus goods.

One of the benefits of their services was refrigeration, and from what I can gather, they also sold chemicals used in refrigeration to businesses in need. This led to overall diversification, and by the late 1930s, Gullatt had dropped the M. & M. name in favor of his own and was apparently just selling various chemicals.

At 21 Haynes, Atlanta Paper Company (APACO) established the headquarters of its new Specialties Division in 1944.

APACO was established in 1868 as the Elsas May Paper Co. and reorganized in 1886 as Atlanta Paper Company. The new Specialties Division focused on large-scale sales to wholesalers and retailers, and its headquarters on Haynes featured a warehouse and display room.

Both companies were founded in 1924 by Jewish immigrant Morris Abelman, who came to the U.S. from Russia in 1901. Puritan Mills manufactured animal feed like My-T-Pure Pig & Hog Ration.

As you might have guessed, Atlanta Flour & Grain processed and distributed flour and grain, but what you might NOT have guessed is that they also distributed roofing materials.

|

| The Atlanta Constitution | Sept. 8, 1924 |

This ultimately led to various subsidiaries (all of which were based out of this building) including Industrial Roofings Inc., Home Insulation Company, and Georgia Roofing Supply Company.

|

| The Atlanta Constitution | Sept. 3, 1932 |

(If you noticed the discrepancies in the addresses in some of the images, it’s because street numbers in Atlanta changed in the 1920s. It’s a whole thing…)

Right next door to all this was the Tuno Packing Company, founded by I. J. Paradies and M. Rich (no relation to Rich’s department store as far as I can tell). Tuno began as distributors of peanut butter, jellies, and condiments but expanded to wholesale grocery and tobacco dealers. The company later changed its name to Paradies & Rich.

|

| The Atlanta Constitution | Feb. 20, 1927 |

By 1938, Nabisco had given up on the Frank E. Block property. Their planned $2 million renovation ended up being a new factory near Fort McPherson that opened in 1942. After Nabisco left the property, Davison’s department store used the building as a surplus warehouse and outlet (their big store was on Peachtree, which you can read about in the Westin Peachtree Plaza post on this very blog).

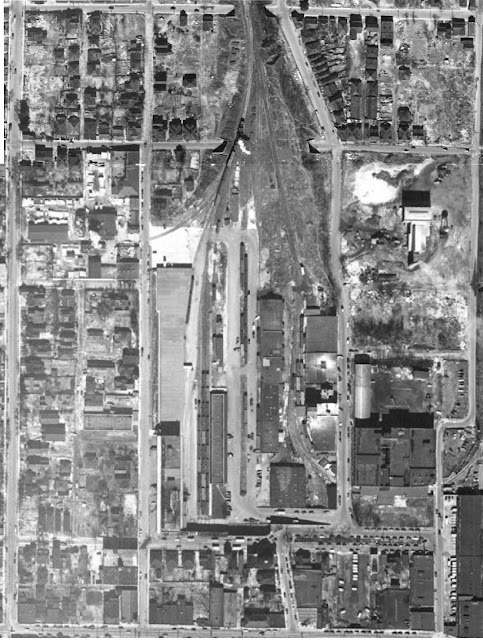

In the aerial photograph below, we get a great view of the area in 1949.

|

| Planning Atlanta - A New City in the Making, 1949 Georgia State University Library |

Here we can clearly see the railroad embankment down the middle of the blocks and the tunnels that run underneath it for Foundry and Magnolia Streets.

|

| "Then I'll dig a tunnel from my window to yours" |

It's also worth noting Magnolia Street went under another tunnel on the east side of the area that was a major artery for west side residents to get to Downtown.

We are also seeing a bunch of vacant lots showing up in the northern blocks. A big reason for this is that much (if not all) of the area was at this point zoned for industry. This meant that no new homes could be constructed, and if a home was left vacant it would be demolished. Landlords then wouldn’t invest too much capital into maintaining homes in the area as a result. This will come up again later...

The AB&C Railroad was now the Atlantic Coast Line and sold vacation packages out of an office on Haynes.

|

| The Atlanta Constitution | June 15, 1954 |

Over on the east side of the area, one lot has a new building replacing almost everything else on the block.

|

| Note the tunnel over Magnolia at the top right leading to Downtown |

In 1941 the city built its new garbage incinerator here. It cost $500,000 and was called “a thing of beauty and absorbing interest” by The Atlanta Constitution. It stood at six stories with a 200-foot smoke stack.

|

| Photo by Kenneth Rogers, undated Atlanta History Center | Kenan Research Center |

Here’s how it worked:

A bay of wide doors allowed garbage trucks to bring the refuse up to the building, where directly inside was a large pit 20 feet deep that the trucks would dump their waste into.

|

| Bay doors with pit The Atlanta Constitution | Sept. 14, 1941 |

|

| Clamshell bucket hauling trash Photo by Kenneth Rogers, undated Atlanta History Center | Kenan Research Center |

The trash then moved to large rotary kilns that spun it around while it burned, reducing it in volume by 80%.

|

| Rotary kilns The Atlanta Constitution | Sept. 14, 1941 |

|

| Control room The Atlanta Constitution | Sept. 14, 1941 |

During World War II, the city held a massive scrap metal drive to support the war effort. Scrap from around the city was collected in a gigantic pile at the incinerator.

Later in 1949, work began on an expansion of the incinerator, doubling it in size with a second smokestack. In 1962, a second incinerator plant was under construction on Jackson Parkway in northwest Atlanta. At that time it was decided to name the new incinerator after Mayor William B. Hartsfield, while the old one here on Magnolia was named after Charles W. Mayson, the incinerator’s late superintendent.

The Mayson Incinerator ran 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. While the plant was in operation, the stacks never stopped spewing noxious smoke into the neighborhood.

Meanwhile, on the southern end of the block, infrastructure was about to get a major upgrade. With highway construction underway in the 1950s, surface streets were sometimes widened or otherwise retooled to accommodate traffic around town. The city wanted bigger, badder roads to get over the railroad gulch to the east of our blocks. The plan was to widen Hunter Street and elevate it with a viaduct, and then have a new Techwood Drive viaduct extend across the gulch from the northeast, intersecting Hunter and then continuing to Mitchell Street. Hunter and Mitchell would also get a bypass between them.

All this meant that the city needed to gobble up some of the existing property to make room for the new road construction. In 1955 Mount Vernon Baptist was informed it would have to move out of the old Temple Baptist property.

|

| Looking north on Mangum toward Mitchell and Hunter, 1955 Lane Bros Commercial Photographs | Georgia State University Library |

Mount Vernon vacated their property in 1960, but a new church hadn't been built yet. Ground was broken for a new church in 1961, but until it was finished the congregation used St. Stephens Missionary Baptist Church's facilities. The new Mount Vernon Baptist Church was completed a couple blocks west on Hunter Street in 1963 (still in our area).

The road construction was delayed for various reasons but was finally completed around 1962. In the following photo looking east toward Downtown, you can see the big new intersection of Techwood (running left to right) and Hunter (running toward the bottom).

|

| Photo by Floyd Jillson, 1964 Atlanta History Center | Kenan Research Center |

The bottom third or so of this photo is our area. The bottom right corner is the area where the old Temple Baptist/Mt. Vernon Baptist was recently demolished. Just to the left of the big intersection is the Frank Block/Nabisco/Davison's building. A bit to the left of that is the Mayson Incinerator. Just below all that is the railroad with its various warehouses.

Speaking of Davison's, the last reference I could find to them being in that building was in 1956. In 1960, the Duke Tire Company set up their new location in the building. Duke Tire had stores all around town, but those were smaller retail shops. This building was their tire recapping plant.

|

| The Atlanta Constitution | Jan. 18, 1960 |

|

| G. T. Duke (right) showing off one of his tires at the new factory's grand opening The Atlanta Constitution | Jan. 18, 1960 |

Duke Tire wasn’t in the building for too long, however, and by 1969 it was abandoned. That December, it was gutted in a six-alarm fire. The fire started in two places leading investigators to believe that it may have been intentionally set.

|

| The Atlanta Constitution | Dec. 30, 1969 |

I found two WSB news videos showing the fire and its aftermath. The first video shows the burning building and spectators watching from the Techwood viaduct.

The second video shows the aftermath of the fire and the charred remains of the old building.

|

| Photo by Floyd Jillson, 1971 Atlanta History Center | Kenan Research Center |

Let’s shift focus back to housing for a bit. In 1968, a photographer named Herbert Lee went around the city and captured photos of some of the conditions the poorest residents endured. He came to the area around Mangum and Magnolia and captured the following shots of housing conditions on Mangum. The photos were taken from the railroad embankment facing east.

|

| Photo by Herbert Lee, 1968 Atlanta History Center | Kenan Research Center |

|

| Photo by Herbert Lee, 1968 Atlanta History Center | Kenan Research Center |

As you can see, conditions here had gotten pretty bad. Many of the residents in the area were renters, with landlords doing little or nothing to improve housing conditions for their tenants.

In January of 1966, white resident Hector Black, an anti-poverty activist and founder of the Vine City Council, began distributing blankets to residents of an apartment building on Markham Street (just south of our area, one street south of Mitchell), who were living without heat. When he returned the next day to help the residents organize a meeting to discuss their housing conditions, landlord slumlord Joe Shaffer, who owned several properties in the area, had him arrested for trespassing. Hector Black and others argued that it was often the tenants who were reprimanded for poor housing conditions, while landlords were not held accountable for their properties and continued charging rent.

Later that week, residents alarmed by recent evictions organized a rent strike and petitioned Mayor Ivan Allen, Jr. to ensure that housing conditions improved. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. arrived to tour the area amid protests of Black’s arrest, and declared it the “worst slum” he’d ever seen. Mayor Allen didn't condone the rent strike but pledged to provide assistance to the tenants. Shortly thereafter, a building inspector declared the homes uninhabitable and the Atlanta Housing Authority promised to find better homes for the tenants.

Since no new housing could be built in this area due to the industrial zoning restrictions, this just meant more empty lots and abandoned businesses. This former storefront on the corner of Magnolia and Mangum was inhabited by the Church of God of the Prophecy as of 1970.

|

| Photo by Tom Coffin | Feb. 14, 1970 Georgia State University Library |

The remainder of the lot is increasingly vacant. In the photo below, the row of homes behind the little church is the same row featured in Herbert Lee’s photos above. The houses to the storefront church's right in the first photo below from 1968 are gone in the following 1970 photo.

|

| Photo by Herbert Lee, 1968 Atlanta History Center | Kenan Research Center |

|

| Photo by Tom Coffin | Feb. 14, 1970 Georgia State University Library |

| ||

Photo by Tom Coffin | Feb. 16, 1970

Georgia State University Library

|

Mayor Sam Massell touted its closure in his reelection campaign the following year (he lost to Maynard Jackson, though).

|

| Photo by Floyd Jillson, 1977 Atlanta History Center | Kenan Research Center |

|

| Photo by Bud Skinner | June 3, 1976 Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographs | Georgia State University Library |

|

| Andre Steiner is excited about his plan The Atlanta Constitution | July 5, 1976 |

|

| Photo by Joey Ivansco | Jan. 6, 1989 Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographs | Georgia State University Library |

|

| Photo by Dwight Ross Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographs | Georgia State University Library |

|

| Photo by Dwight Ross Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographs | Georgia State University Library |

This is amazing! Thank you!

ReplyDeleteYou may have seen this post from a decade ago about the area just a few blocks north. https://returntoatl.blogspot.com/2012/01/before-georgia-dome-world-congress.html

ReplyDeleteThis is such a great post. Thanks a lot to sharing most valuable information about Party Planner Decatur .

ReplyDelete