Hello there!

Halloween is recently behind us, and there's no scarier story than that of Atlanta's urban development. So join me by the campfire for a bone-chilling tale of vacant lots and abandoned buildings...

Today's block is right across the street from the Five Points MARTA station in the historic heart of the city.

The boundaries aren't always apparent because a major feature of the block has been railroad tracks and viaducts. Today I am saying it is bounded by Forsyth Street, Alabama Street, Ted Turner Drive (formerly Spring Street), and Wall Street.

We begin our tale in the antebellum days and this 1853 map.

Immediately it’s hard to see what we’re supposed to be looking at because there’s no real block to speak of. But the pieces that I am saying belong to us are boxed in below.

The dotted lines are the railroads. That wedge-shaped bit in the bottom right will become important soon, but right now let’s focus on the building marked ‘B’. That would be the freight depot for the Western & Atlantic Railroad.

|

| Western & Atlantic Freight Depot, 1863 Atlanta History Center | Kenan Research Center |

As some of you may know, Atlanta was founded in 1837 as the terminus of the Western & Atlantic Railroad, giving the city its original name. A settlement developed around the railroad, and the town was incorporated as Marthasville in 1842, then Atlanta in 1847.

When the Union Army occupied Atlanta in 1864, they made sure to cut off the Confederacy’s supply lines by destroying things like railroad depots. So the W&A depot here was ultimately toast.

|

| Shortly before its destruction, 1864 Library of Congress |

After the war, Atlanta was quick to rebuild, and a new depot was erected right where the old one was, as you can see in the 1871 birds eye drawing (‘E’ in the image below). The building also housed the offices of the superintendent and various other railroad officials.

|

| 1871 |

Here we can also see that little wedge of property now has a few little buildings on it (the choo-choo is passing between it and the depot). You can see it in the photo below, looking south along Forsyth Street.

|

| 1870s Atlanta History Center | Kenan Research Center |

Our wedge is just to the right of Forsyth on the far side of the tracks. The depot is just out of frame to the right. The buildings in the foreground are different blocks on the north side of the tracks.

In the 1878 atlas below, the little buildings are gone and replaced by Alexander T. Cunningham’s new warehouse building (the shaded portion).

|

| 1878 |

According to the Atlanta Constitution, that building’s construction was already underway in September of 1875 at a cost of $25,000, and it was ready for tenants by December of that year.

|

| Atlanta Constitution | Dec. 17, 1875 |

The earliest tenants of the Cunningham Building I could find, however, are in 1882. First, we have B. F. Avery & Sons, a wagon, buggy, and carriage shop.

|

| Atlanta Constitution | Apr. 2, 1882 |

Then we have Walton, Whann, and Co., manufacturers of fertilizers based out of Wilmington, DE, who according to the ad below appear to be vacating the building soon.

|

| Atlanta Constitution | Oct. 15, 1882 |

|

| Historic poop mongers Atlanta Constitution | Feb. 18, 1874 |

By 1886, the Cunningham Building had expanded to fill the entire wedge of land, as we can see in the Sanborn map below:

|

| 1886 |

The 1892 Sanborn map looks largely the same, but we see John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company at the east side of the building.

|

| 1892 |

This was a storage facility for Standard Oil, and in case you were wondering, yes it did catch on fire. A pile of trash “spontaneously combusted” in 1890, according to The Constitution...

...but the fire department managed to put it out before any of the oil ignited.

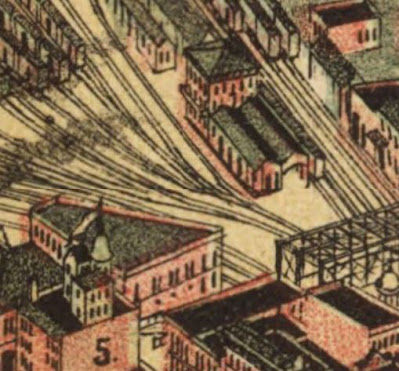

Next, the 1892 birds eye view gives us a look at a major infrastructure upgrade attached to our block.

|

| 1892 |

Taking a moment to orient ourselves, the number 5 in the image is not our block. But the wedge-shaped building directly behind it is our Cunningham Warehouse. Then in the middle of the railroad tracks is the Western & Atlantic freight depot. The infrastructure upgrade I spoke of would be the bridge we see stretching across the tracks toward the right side of the image.

Completed in July of 1893, the Forsyth Street Bridge connected Alabama and Marietta Streets, allowing pedestrians and carriages to safely cross over the railroad tracks, which had become increasingly dangerous as the city grew.

The bridge was of further benefit to Atlanta, apparently, because the railroad tracks had physically divided Atlanta into two sections, which led to the city developing two distinct social and political areas. The new bridge, according to a July 2, 1893 article of The Constitution, “forms a link between the two sections of the city which will not only bring the two sections closer together, but has had a large tendency to wipe out the feeling of division.”

|

| 1897 Atlanta History Center | Kenan Research Center The building in the distance is across the tracks from our block. |

Reports of another fire in 1897 tell us a bit about the Cunningham Building’s tenants at the time. We’ll go through the various occupants of the building first and then talk about the fire.

First, at 29 Alabama we have Camp Brothers, a wholesale feed company founded by Milton and Daniel Camp (Milton also served on Atlanta’s City Council).

Also at 29 Alabama was Whitcomb & Son, merchandise brokers specializing in meat and lard. Joseph T. Whitcomb was born in Vermont in 1833 and made his way to Atlanta in 1886. He started his business with his son, H. H. Whitcomb in 1887. Joseph died in 1902 and his son kept the business going.

|

| Joseph T. Whitcomb Atlanta Constitution | Mar. 2, 1902 |

Also also at 29 Alabama (getting crowded here) was Sumner W. Bacon Fruit Co., known for the “Lord Bacon” watermelons grown in DeWitt, GA (nearby Baconton is named for the family).

Next door at 31 Alabama was Dodge & Heard, commission merchants dealing in hay, grain, and lard.

On the second floor of 31 was Grant Sign and Mirror Works, which as the name implies crafted signs and mirrors. It was founded by Edward L. Grant around 1890.

|

| Atlanta Constitution | Oct. 8, 1917 |

At 33 Alabama was the G. H. Hammond Packing Company, which distributed meat from Indiana, Nebraska, and Illinois.

And then the rest of the building was occupied by White Hickory Wagon Company, which was incorporated in 1893 and would eventually move to Broad Street in 1900.

So anyway, the fire started in the basement storage area of Dodge & Heard. The cause is a mystery, but it is speculated that maybe a spark from the railroad came in through an open window and landed on some flammable material. Or maybe it was spontaneous combustion, I don't know. Even though the fire station was across the street, the smoke from the fire mixed with steam from the trains and went unnoticed for a while. By the time smoke started billowing from the front doors, the fire was already raging through the basement. The fire department worked for three hours to put it out.

|

| Fire Station across the street at 44 Alabama Nov. 16, 1916 Atlanta History Center | Kenan Research Center |

Camp Brothers, Whitcomb & Son, and Grant Sign & Mirror appear to be hit the hardest by the fire. White Hickory Wagon was spared completely by a firewall that separated the original portion of the building and the expansion that they occupied. Most of the damage was to the various companies’ stock, which was pretty much all insured. The building suffered interior damage, but the overall structure survived.

Despite being insured, Camp Bros ended up going broke by the end of 1898. Certainly not helping them was ANOTHER fire on Nov. 30 of that year. This one was caused by an employee knocking over a kerosine stove and spilling liquid hot death all over the basement of Whitcomb & Son, where Camp Bros had some of their stock stored. A new firewall installed after the last fire kept this one from spreading to the rest of the building, and the damage was limited to some of both companies’ stock.

I would love to tell you that was the last fire this building would suffer. But I would be lying.

For now, let’s turn our attention to the 1899 Sanborn map, where we see much of the same as before with one major exception.

|

| 1899 |

Yes, the Western & Atlantic freight depot is gone. The railroad offices had already moved to the Austell Building on the north side of the tracks (it’s the building on the other side of the Forsyth Street bridge in the photo from earlier), and the demolition allowed for more tracks to be laid.

In our fire-prone building, we now have the Carhart Shoe Manufacturing Company, founded by W. B. Carhart, who came to Atlanta from Macon in 1892.

Also in that building at this time was Cay, Parrott & Co. at 35 ½. These were cotton dealers founded in 1896 by John E. Cay and George W. Parrott, Jr. Parrott sold his interest in the firm to his father, George Senior, after only one year in business in August 1897. A few days later, George Parrott, Jr. took his own life. The Atlanta Constitution published an account of Parrott’s last day. Jump ahead to the image below if you’d prefer to skip it, but the story goes:

In the months before his death, George Jr. had lost a significant sum of money on bad investments, first in the Jersey Central Railroad, and then the rest in a failed attempt to make that money back in the sugar and wheat markets. The afternoon before he died, he spoke with a reporter at the Atlanta Constitution about his losses, which he estimated at close to $100,000. Downplaying the situation, Parrott said that he would soon be traveling to New York to begin paying off his debts.

But later that day, he met a friend, John Johnson, at the Cay, Parrott & Co. offices here on West Alabama Street to crunch some numbers, and he discovered that he owed more than he originally believed. Distraught, Parrott revealed a pistol and put it to his head, but Johnson was able to grab the gun away from him before he pulled the trigger. Johnson and Parrott then spent the night walking around the city together, and after some time Parrott assured his friend that he would not make another attempt.

Parrott returned to his home on Howard Street just after 1:00 am. His mother-in-law heard him moving around the house, and went downstairs to check on him. As she approached the dining room, she heard a gunshot, and found Parrot on the floor moments later. He had placed two pillows on the floor and laid his head down before shooting himself in the temple. He was 23.

|

| Atlanta Constitution | Aug. 29, 1897 |

Moving along to the 20th Century, we have yet another fire to discuss. This one started the morning of February 19, 1906 in the basement of the A. C. Wooley wholesale grain company at 33 West Alabama, where a lit candle tipped over onto a bunch of hay because of course it did. Smoke from the fire began filling the building, making for a particularly harrowing experience for employees of the Bostrom-Brady Manufacturing Company at 31½ on the second floor. Most of the employees made it out on foot, but two people trapped by worsening smoke were ultimately rescued through windows by firefighters with ladders. A. C. Wooley lost a bunch of hay to the fire, and Bostrom-Brady experienced some smoke and water damage, but things were otherwise not too bad.

|

| Atlanta Constitution | Feb. 20, 1906 |

Bostrom-Brady, by the way, was a machine and tool manufacturing company founded in Atlanta by Swedish-born Ernst Alfred Bostrom in 1901. Bostrom was particularly well-known for designing a simple and affordable level. The Smithsonian has one in its collections at the National Museum of American History, which you can see here.

Bostrom-Brady wouldn’t remain in our building for long, but it seems the company lasted quite a while. I found newspaper ads all the way into the 1980s.

Looking back at the image of the fire above, it’s hard to make out, but you might be able to see the sign for Albright & Prior Grocers. They moved in around 1902 but were bought out by the Oglesby Grocery Co. some months after the fire.

Moving to the 1911 Sanborn map, we again see a lot more of the same.

|

| 1911 |

Railroad tracks take up much of the area, with our wedge-shaped building at the southeast containing some hay and some groceries.

One notable tenant around this time was German-born horticulturist and landscape architect Otto Katzenstein, who came to Atlanta from Boston in 1903.

|

| Atlanta Constitution | May 12, 1914 |

Katzenstein initially arrived as a member of the Olmsted Brothers firm commissioned to implement the plans of the brothers' father, famed landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, for the new Druid Hills neighborhood east of Atlanta. Once here, Katzenstein set up his own horticulture business, which was briefly housed in our building here on West Alabama. He died in 1934. His wife, Carolyn Kraushaar Katzenstein, was a charter member of the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra. She died in 1944.

|

| Atlanta Constitution | Sept. 23, 1909 |

There are plenty of other commercial tenants I could mention, but to keep things from getting tedious (too late?), let’s jump ahead to the 1919 bird’s eye view.

|

| 1919 |

It’s a bit busy, so here’s our block (ish) outlined to make things easier.

Wrigley Engraving was founded by William H. Wrigley, a Philadelphia native who came to Atlanta in the 1890s to run The Atlanta Journal’s stereotyping department. After about 10 years there, he started his own engraving company. He ultimately retired and left his company in the care of his four sons. He died in 1928.

|

| Macon Daily Telegraph | Aug. 10, 1915 |

The images from the old newspaper aren't the best quality, but here are some close-ups anyway for good measure.

|

| Atlanta Constitution | Feb. 3, 1913 |

We still haven’t really seen a decent photo of the Cunningham building, and that is no different in the 1922 photo below:

|

| 1922 Atlanta History Center | Kenan Research Center |

Our building is peeking out of the bottom left corner. That would be the Everett Seed Co. side. We do get a nice look at the Forsyth Street viaduct here, though, which will get a significant upgrade by the end of the decade. More to come there.

1922 also brought a notable new tenant to the building with the Donaldson-Woods Printing Company.

|

| Atlanta Constitution | Nov. 5, 1922 |

|

| Atlanta Constitution | Nov. 5, 1922 |

This company also brings us our best look at the building to date via an advertisement in The Constitution.

|

| Atlanta Constitution | Nov. 12, 1922 |

And this 1929 aerial shot, where we can see our block in the bottom left corner.

|

| 1929 Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographs | Georgia State University Library |

Okay, now let’s get into the fun stuff.

A few blocks east of us, down the railroad tracks, sat Atlanta’s Union Station.

|

| Old Union Station | Nov. 19, 1927 Photo by Edgar Orr Atlanta History Center | Kenan Research Center |

The passenger railway depot was built in 1871 on the site of the original Union Station, which burned during the Siege of Atlanta. By the mid-1920s, the second iteration of Union Station was getting a little long in the tooth. It needed renovations, but it was also too small for the traffic it was getting. Officials began eyeing a new location for the station, and yes, the Forsyth Street viaduct here on our block was chosen for the new Union Station. The main building would stand atop a newly expanded viaduct and plaza over the tracks, with stairway access to the platforms below. Designed by McDonland & Company, construction began in 1929 with Southern Ferro Concrete Company as builders.

|

| Union Station Construction, looking west | Nov. 5, 1929 Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographs | Georgia State University Library |

|

| Union Station Construction, looking west | Jan. 9, 1930 Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographs | Georgia State University Library |

|

| Union Station construction, looking north | 1930 Atlanta History Center | Kenan Research Center |

In order to construct the newly expanded viaduct, the existing one had to be temporarily torn out.

|

| Apr. 14, 1930 Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographs | Georgia State University Library |

That photo gives us a pretty good view of the backside of our old Cunningham building (the one on the right). We clearly see Everett Seed and if you can make out some of the other businesses named on the building, they are Grant Sign Company (who we already met) and Kingan & Co.

Kingan was a meat and lard dealer that sold its “reliable” bacon.

|

| Atlanta Constitution | Apr. 22, 1938 |

Anyway, Atlanta’s third Union Station was completed in 1930.

|

| June 1946 Photo by Tracy O'Neal Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographs | Georgia State University Library |

If we look at the 1931 Sanborn map, we can see how the overall block is changed by the addition of Union Station.

|

| 1931 |

It might be a little tricky to process that black-and-white image of the map, but I am here to help. We have, starting at the bottom on Alabama Street, the wedge-shaped Cunningham building that we should all be very familiar with by now. On the right we have Forsyth Street, which in this map is shaded with diagonal lines to indicate that it’s an elevated viaduct crossing over the train tracks. Follow that north and we see the newly expanded viaduct extending westward, on top of which is the new Union Station. To the west of the main Union Station building are steps that descend to the platforms adjacent to the tracks.

Not long after it opened, Union Station received a particularly noteworthy passenger. In October of 1932, Democratic nominee for President, Franklin D. Roosevelt, arrived on a campaign tour and was greeted by a crowd of 25,000 people at Union Station. He would, of course, go on to win the election a month later.

|

| 1932 Photo by Kenneth Rogers Atlanta History Center | Kenan Research Center |

|

| 1932 Photo by Kenneth Rogers Atlanta History Center | Kenan Research Center |

|

| 1932 Photo by Kenneth Rogers Atlanta History Center | Kenan Research Center |

|

| 1932 Photo by Kenneth Rogers Atlanta History Center | Kenan Research Center |

More big changes came to the block in the 1940s. To start the decade off, The Atlanta Constitution bought the Cunningham building property with plans to erect its new headquarters in its place. This meant tenants like Everett Seed, at this location for over 25 years, had to vacate.

The existing Constitution Building was across the street diagonally from the Cunningham building and was built in 1884. That building, whose offices at one time held the likes of Henry Grady and Joel Chandler Harris, was showing its age for its tenants. Elevators were sluggish and the old wiring was prone to starting small fires.

|

| Old Constitution Building, 1890 Art Publishing Company Atlanta History Center | Kenan Research Center |

In the following photo, the Cunningham building is gone, and construction of the new Constitution building is underway. Looking southeast, we can see the old Constitution building (the darker one) sandwiched between Rich’s department store’s buildings. Constitution staff members watched their new building go up in real time and would venture across the street to explore the new site and put pennies in the wet concrete.

|

| 1947 Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographs | Georgia State University Library |

Designed by Robert and Company, the new art moderne building was completed and occupied by the Constitution’s offices in December 1947, with the last edition of the newspaper coming out of the old building published on December 28.

|

| ca. 1947-1948 Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographs | Georgia State University Library |

|

| 1947 Photo by Bill Watson Atlanta History Center | Kenan Research Center |

|

| 1948 Lane Bros. Commercial Photographs | Georgia State University Library |

Despite the need and excitement for new facilities, vacating the old building was met with sadness, particularly from the more veteran employees of the Constitution. Black arm bands were worn on moving day to represent the staff in mourning.

|

| 1947 Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographs | Georgia State University Library |

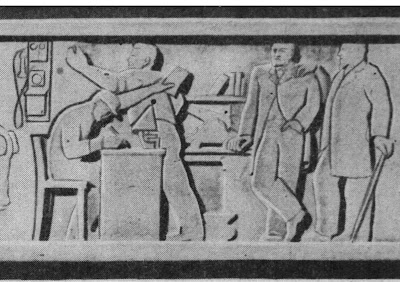

Over the summer of 1948, a large relief sculpture was carved above the main entryway along Forsyth Street. Designed by sculptor Julian Harris, the frieze depicts scenes of the Atlanta Constitution’s relationship with Atlanta history. Harris made large plaster models of the reliefs, and then hoisted them up scaffolding to copy them directly into the stone.

|

| Julian Harris with plaster model Atlanta Constitution | Jan. 11, 1948 |

At one point, Constitution editor Ralph McGill tagged in to help with the carving.

|

| Julian Harris (left) watches Ralph McGill carve a portion of the sculpture Atlanta Constitution | June 27, 1948 Photo by Hugh Stovall |

The final relief was six feet high and 72 feet in length.

| Atlanta Constitution | Dec. 5, 1948 |

The individual scenes depicted include an old flat-bed press used by the newspaper when it started in 1868:

Union troops leaving Atlanta at the end of Reconstruction, depicted across the first Constitution building (this new one would be the third):

The special train that delivered the newspaper to Macon and West Point beginning in 1872:

Characters from the Uncle Remus tales famously published by former Constitution journalist and editor Joel Chandler Harris:

Former editor Henry Grady and owner Evan Howell watching in 1885 as word comes via telephone that Grover Cleveland was elected the first Democratic President in 25 years:

The entryway to the last Constitution building:

An agricultural scene highlighting mechanized farming:

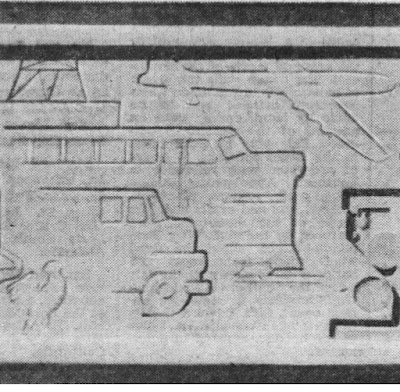

The various transportation methods that bring newspapers to the people:

And finally, a modern printing press with the newspaper staff that contributes to the process:

A dramatization of the story depicted on the relief aired on WCON, the Constitution’s new radio station operated out of the building.

|

| 1950 Atlanta History Center | Kenan Research Center |

|

| 1949 Southern Labor Archives | Georgia State University Library |

|

| New escalator at Union Station Photo by Bill Mason Atlanta Constitution | Jan. 15, 1946 |

Then in January of 1948, the Freedom Train arrived at Union Station on its tour of about 300 American cities. The red, white, and blue train held an exhibit of over 100 historic documents related to US history, including original versions of the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, the Bill of Rights, and the Emancipation Proclamation (all of which is somewhat horrifying to me as an archivist). It had seven cars, three of which held the exhibits, with the remaining four used for maintenance and to house the Marines assigned to guard the records on board.

|

| U.S. Marines and Atlanta Police guarding the Freedom Train | Jan. 1, 1948 Photo by Jimmy Fitzpatrick Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographs | Georgia State University Library |

The exhibit was open for two days from 10am-10pm, and the line to get in wrapped around the block, averaging a two-hour wait in the cold and rain. In the deeply segregated South, the Freedom Train’s governing body required access to be racially integrated. Memphis and Birmingham demanded segregated lines or entry times, but the Freedom Train’s response to those demands was to skip those cities entirely.

|

| Jan. 1, 1948 Photo by Jimmy Fitzpatrick Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographs | Georgia State University Library |

|

| Jan. 1, 1948 Photo by Jimmy Fitzpatrick Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographs | Georgia State University Library |

Not everyone made it in time, as seen in the photo below. Inside Union Station, the police are guarding the doors to the platform after the Freedom Train exhibit had closed.

|

| Jan. 1, 1948 Photo by Jimmy Fitzpatrick Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographs | Georgia State University Library |

For those that did make it in, a scroll was available to sign, acknowledging the rededication pledge accompanying it. The pledge read:

“I am an American

A free American

Free to speak–without fear

Free to worship God in my own way

Free to stand for what I think

Free to oppose what I believe wrong

Free to choose those who govern my country

This heritage of Freedom I pledge to uphold

For myself and all mankind.”

The signed scrolls were presented to President Harry Truman at the end of the train’s tour before ending up in the Library of Congress.

|

| A boy signs the pledge | Jan. 1, 1948 Photo by Jimmy Fitzpatrick Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographs | Georgia State University Library |

If you are interested in learning more about the Freedom Train, you can visit the Google Arts & Culture page on it, which has lots of nifty information and photos, particularly in relation to the exhibits (all those precious documents had to be insured, naturally).

You can also check out this website for lots of information on the train itself, as well as some of the memorabilia associated with the train’s tour.

Getting back to our block, let’s take a look at the 1949 aerial photo below:

|

| 1949 |

Now we see the new Constitution Building in place of the old Cunningham Building, but we see that the Constitution Building has maintained some of the wedge shape of that portion of the block. The new building is casting a shadow across the train tracks between it and Union Station.

In 1950, there was a pretty big development at The Constitution. In a joint statement published on March 19, Clark Howell, publisher of the Constitution, and James Cox, chairman of the Atlanta Journal, announced that the two newspapers would be merging. They would maintain their separate editorial staffs and identities, with the Constitution as the morning paper, the Journal as the evening paper, and a combined edition on Sundays. The deal was finalized and the new company was chartered on May 31.

Leadership of the newspapers claimed the merger would mean a bigger budget to report the news. But this also meant that the Constitution offices would be moving again already! The Atlanta Journal had also recently built a new building, and the decision was made that their facility would be best to house everyone under one roof. By the end 1951, the Constitution had mostly vacated the building that they occupied for only about three years.

Here are some of the front pages published during the Constitution’s short time in the building:

|

| Jan. 31, 1948 |

|

| Aug. 12, 1949 |

|

| Sept. 8, 1949 |

Meanwhile, as the Constitution was making their way out of the building, a new temporary tenant came in 1950. As the Korean War ramped up, the Army and Air Force Recruiting Processing Center at Fort McPherson was getting overwhelmed. Needing a new space, the operation moved to the ground floor of the Constitution Building.

|

| New recruits waiting in the Constitution Building Atlanta Constitution | Jan. 5, 1951 Photo by Carl Dixon |

|

| New recruits waiting in the Constitution Building Atlanta Constitution | Jan. 5, 1951 Photo by Carl Dixon |

Fittingly, as the Korean War came to a close in 1953, many soldiers returned home via Union Station next door.

|

| Photo by Bill Wilson | Sept. 2, 1953 Atlanta History Center | Kenan Research Center |

|

| Photo by Bill Wilson | Sept. 2, 1953 Atlanta History Center | Kenan Research Center |

With the Constitution out, Georgia Power Company took over the building for their Atlanta Division Office, making this the building where lots of Atlanta residents paid their power bills.

Also around this time, Rich’s Department Store, just across Alabama Street from the Constitution Building, wanted more parking for shoppers. Around 1950, a new three-story deck went up over the railroad tracks between the Constitution Building and Union Station.

|

| Top left area is us Photo by Ryan Sanders | ca. 1950 Atlanta History Center | Kenan Research Center |

|

| Feb. 28, 1953 Lane Bros. Commercial Photographs | Georgia State University Library |

|

| 1953 Atlanta History Center | Kenan Research Center |

|

| Note the new Georgia Power sign on the former Constitution Building Nov. 30, 1954 Lane Bros. Commercial Photographs | Georgia State University Library |

Back at Union Station, big changes came in 1956 when the Interstate Commerce Commission ordered all waiting rooms in train and bus stations to be integrated. All segregation signs were taken down at Union Station on January 10th.

|

| Photo by Joseph C. Fisch, 1954 Atlanta History Center | Kenan Research Center |

This directive did not, however, apply to the lunch counters at train stations, which remained segregated. This ultimately led to nearly 200 Black college students staging sit-ins at 10 white eateries across Atlanta on March 15, 1960. At Union Station, nine students sat down and asked for service. The police were called, and when the students refused to leave, they were arrested. The demonstrations that day led to 77 total arrests. One of the nine students arrested at Union Station was a 16-year old Morehouse freshman from Birmingham. Fulton Juvenile Court Judge W. W. Woolfolk ordered him to return home, telling his parents if they “can’t control him in Atlanta, then you will have to take him back to Birmingham.”

|

| Sit-in at Union Station | Mar. 15, 1960 Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographs | Georgia State University Library |

|

| Sit-in at Union Station | Mar. 15, 1960 Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographs | Georgia State University Library |

|

| Sit-in at Union Station | Mar. 15, 1960 Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographs | Georgia State University Library |

|

| Sit-in at Union Station | Mar. 15, 1960 Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographs | Georgia State University Library |

|

| Sit-in at Union Station | Mar. 15, 1960 Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographs | Georgia State University Library |

Atlanta's lunch counters ultimately desegregated in September of 1961.

Moving on, we now begin the sad tale of our block's decline...

|

| 1967 Georgia State University Library |

Throughout the 1960s, passenger rail travel had sharply decreased nationwide due to a combination of factors including increased automobile travel spurred by the interstate highway system, increased air travel, and railroad companies prioritizing commercial freight with better profit margins.

By 1967, only one passenger train was coming through Union Station, an Atlanta-to-St. Louis train called ‘The Georgian’ operated by the Louisville & Nashville Railroad Company.

|

| ca. 1940s Image found at Streamliner Memories |

That train was used by only about one or two dozen passengers a day by 1969, though, so in July of that year, L&N Railroad requested permission from the Interstate Commerce Commission to discontinue service for the line. That request was initially denied by the ICC, who argued that service had declined due to L&N’s neglect.

|

| Station Master C. W. Turner chats with the conductor of The Georgian, 1970 Photo by Joe McTyre Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographs | Georgia State University Library |

Still, the overall emptiness of Union Station was a noticeable issue, with one Constitution journalist referring to it as a “toilet for vagrants” (July 7, 1969). Regardless of the ultimate fate of L&N’s last service line, the Georgia State Properties Commission decided to open bids to lease the air rights for the Union Station property in January of 1970.

|

| Atlanta Constitution | Jan. 18, 1970 |

The Commission accepted the only bid they received, which came from Downtown Development Corp., a subsidiary of Cousins Properties, Inc., the firm developing the Atlanta Coliseum (later the Omni). Nothing would happen with the property immediately, but Union Station’s days were officially numbered.

|

| Get your tickets while you can! Photo by Joe McTyre, 1970 Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographs | Georgia State University Library |

In fact, The Georgian would soon discontinue service after all, which would be the final nail in Union Station’s coffin. With the decline of passenger railway service being a national problem, Congress passed the Rail Passenger Service Act in October 1970, which led to the establishment of the semi-public corporation known as Amtrak.

Amtrak allowed railroad companies to offload their passenger service into a federally subsidized corporation, freeing those companies from the obligation of continuing unprofitable services. Amtrak began operations on May 1, 1971, and passenger rail services were immediately slashed all over the country. Among the lines that didn’t survive was The Georgian, which made Union Station officially vacant. Atlanta was left with only one passenger train, which stopped at Terminal Station on its way between New York and New Orleans. Several cities lost all passenger rail services entirely.

With rail service out of the way, possession of Union Station was turned over to Cousins Properties that July. Demolition commenced in August.

|

| Photo by Floyd Jillson, 1971 Atlanta History Center | Kenan Research Center |

|

| Photo by Floyd Jillson, 1971 Atlanta History Center | Kenan Research Center |

|

| Photo by Floyd Jillson, 1971 Atlanta History Center | Kenan Research Center |

An attempt was made to sell off the columns from the station’s facade...

|

| Atlanta Constitution | Aug. 21, 1971 |

...but I couldn’t confirm if anyone bought them or not. They might have ended up in the rubble.

|

| Photo by Charles R. Pugh, Jr. | Oct. 1, 1971 Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographs | Georgia State University Library |

Video courtesy of the Walter J. Brown Media Archives and Peabody Awards Collection at The University of Georgia Libraries.

|

| All gone... Photo by Floyd Jillson, ca. 1972 Atlanta History Center | Kenan Research Center |

Cousins’ plan was to turn the area into a temporary parking lot until more permanent plans could be finalized. In the meantime, construction of the MARTA Five Points Station commenced across Forsyth Street to the east. This meant the Forsyth Street viaduct would close from February until around October of 1976 and be rebuilt to accommodate the new station.

|

| Photo by Guy Hayes | Feb. 9, 1976 Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographs | Georgia State University Library |

In 1979, Cousins Properties CEO Tom Cousins finally unveiled his plan for the former Union Station property, which would become part of an ambitious, sprawling, and ultimately doomed project called Omnisouth. Budgeted at $265 million, Omnisouth would be a 22-acre multi-use development connecting the Omni Coliseum (where State Farm Arena is today) and Omni International (now CNN Center) with Rich’s Department Store across the street from us here to the south. The plan included a shopping mall, luxury housing, office towers, a hotel, a space-needle-style observation tower, and a cable car. Our block here would have been an office tower (the one closest to the bottom right in the image below).

|

| Atlanta Constitution | June 4, 1979 |

Curiously, the plan appears to include the location of the Constitution Building, which I don't believe was part of the Cousins property, and I found no mention of how that was going to be incorporated. The Rich’s parking deck next door was torn down sometime in the ‘70s, if anybody actually cares.

Anyway, the Omnisouth plan had a lot of support from local politicians and business leaders, but many questioned the size and scope of it, suggesting it could be scaled down for a smaller price tag. Others criticized the lack of affordable housing in the plan. With the project relying on $60 million in federal urban renewal grants, making the plan more competitive would increase the chances of receiving funding.

|

| Atlanta Constitution | June 19, 1979 Photo by Willis Perry |

The Omnisouth plan was eventually scaled down to a 15-acre project, but it was still never able to materialize. Funding was never obtained largely because Cousins couldn’t nail down a department store to co-anchor the shopping mall with Rich’s. When J.C. Penney declined in August of 1980, that was pretty much the end of it.

Tom Cousins would never get to be Atlanta’s Brad Wesley…

With Omnisouth dead, Cousins let the property on our block go into foreclosure in 1983. There was an attempt in 1989 to get a convention hotel built here, but that too never got off the ground. Then in 1991, Atlanta Regional Commission began mulling the possibility of a new multi-modal hub for Amtrak and MARTA. But hey guess what? It never happened…

Indeed, the temporary parking lot put in by Cousins in 1971 is still kicking 50 years later.

|

| Aug. 4, 1992 Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographs | Georgia State University Library |

Getting back to the Constitution building for a moment, Georgia Power continued occupying the space through the 1970s, using it as their surplus inventory clearance center.

|

| Atlanta Constitution | Aug. 1, 1975 |

But they vacated the building entirely by 1977. That year, the relief sculpture above the entrance was donated to MARTA for installation in the Techwood station (later the CNN Center station) under construction at the time. It can still be seen there today above the escalators at the station entrance. Next time you’re at State Farm Arena or the Benz and take MARTA via the CNN Center station, check it out as you ride the escalators down into the station.

|

| Photo by Pete Corson, 2018 Atlanta Journal-Constitution |

I’m glad the sculpture has been preserved, but removed from any context it’s kind of pointless hanging out in a MARTA station where no one even really notices it. It’s a very Atlanta thing to do, though.

Back at the building, with Georgia Power gone, the old Constitution building has been vacant for over 40 years now.

A Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) of the building was conducted in the 1980s, which documented its history and architectural significance.

|

| Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) | Library of Congress |

|

| Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) | Library of Congress |

|

| Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) | Library of Congress |

But the building has only further deteriorated since then, with trees growing out of the roof.

|

| 2009 |

|

| Photo by James Getz, ca. 2018 Atlanta Journal-Constitution |

|

| Photo by Pete Corson, ca. 2018 Atlanta Journal-Constitution |

The City of Atlanta bought the building in 1995, but nothing has been done with it so far. In 2016, the city started looking into development options. The following year, developers proposed a $40 million dollar renovation of the site that included a rooftop bar and a new residential building next door.

That deal hasn’t moved forward yet, but as of 2021 it appeared to still be the plan. For now, though, it’s just slowly decaying.

In 2014, photographer Chris Hunt got to take some cool photos of the building’s spooky interior, which you can check out here.

And that’s that! Hoping for a happy ending to this tale sometime soon, but until then, thanks for reading!